Since Antiquity, it has been debated whether the hand or the mind is what makes humans intelligent. My project, situated between the history of technology, the history of science and knowledge, and the history of media, embeds historical practices of testing within those debates, showing that by testing embodied, practical intelligence, psychotechnical experts often consolidated the Cartesian rift between bodily experience and cognition. I analyze psychological apparatus and testing for vocational abilities in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland between the First World War and the 1960s, seeking to answer three questions: What ideas of manual skills and cognitive abilities were inscribed into these test procedures and practices? What skills were considered essential for performing successfully? And how did psychotechnical practices and test apparatus categorize and normalize tacit knowledge?

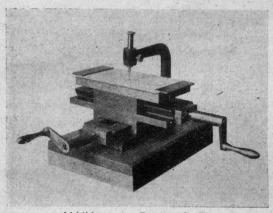

Applying four analytical lenses—materiality, practices, gender, and temporality—to case studies on psychological test apparatus and test practices, I show how the manual and cognitive abilities measured were translated into mutable categorizations and correlations of skills and abilities. That process is exemplified in three psychological devices: Walther Moede’s bimanual tester, mainly used to evaluate metal-industry apprentices in the 1920s and 1930s; wire-bending tests used in vocational counselling from the 1920s to the 1950s; and the “determination device” designed by Karl Mierke, which military and traffic psychologists used in the 1950s and 1960s to evaluate subjects’ ability to react.