Scientists and physicians are not immune to the excesses of enthusiasm, and in the middle of the seventeenth century no single achievement gained more enthusiastic followers than William Harvey’s demonstration of the circulation of the blood. As recognition of Harvey’s achievement spread, so too did a generalized project of identifying other circulations of fluids in living things, both plants and animals. One example is the so-called “neural circulation” advanced by the Cartesian physician Henricus Regius in his Fundamenta physices of 1646. The neural circulation, and with it the “slug experiment” confirming its reality, was accepted across the later speculative and experimental divide. It bears witness to the complex legacy of Cartesianism and experimentation, early modern practices of borrowing novel facts and repackaging them, the eclectic reading habits of natural philosophers, and the perceived value of repeating experiments. This project examines the epistemic context and the evidence that Regius brought to bear in support of the neural circulation. It also attends to subsequent debates about its reality, which did not subside until the eighteenth century, when neural circulation was finally rejected.

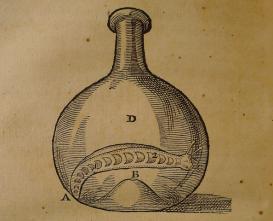

Slug experiment confirming the circulation of animal spirits (H. Regius, Fundamenta Physices, 1646, p. 232). Source: Huntington Library, San Marino, California, RB 474469

Project

(2023-2024)