Visual depictions of heavenly phenomena show how different experts have mixed and altered concepts, structures, and forms, and how they drew on various cultural repertoires and registers of knowledge. We know, for instance, that the dragon’s head is a transformation of the Indian pseudo-planet Rahu, which causes eclipses, but is not linked to a dragon. Pre-Islamic texts from Iran and Syria already talk of an eclipse-causing snake. Whether its head was integrated with slight transformations into Sagittarius’s image there and how Sagittarius came to his feline body are two of the enigmas investigated in this project.

Another enigma was already deciphered. The blue celestial map (Figure 1) was previously identified as a product of an anonymous fifteenth-century artist or astrologer from Iran. However, a careful analysis of the image tells us that it was actually produced there in the seventeenth century.

Fig. 1: Anonymous celestial map of the northern hemisphere, seventeenth century. Bonhams’ catalog Islamic and Indian Art, October 11, 2000, p. 37.

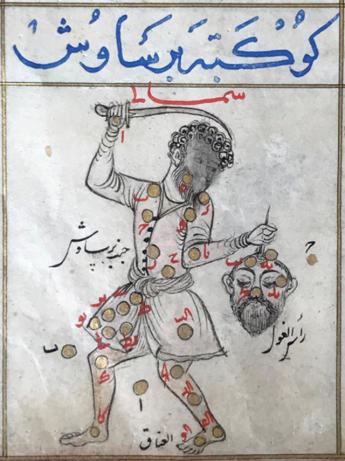

The first pointers to a foreign origin of the map are its numerous nude figures—showing Andromeda, Perseus, Auriga, Gemini, Serpentarius, Aquarius, Cassiopeia, and the human torso of Sagittarius—and the depiction of Aquarius from behind. Clear evidence for a Western European predecessor is the presence of Medusa’s head and the inclusion of Berenice’s hair. Berenice’s hair does not belong to the pictorial canon of star constellations in Islamicate societies, which was established by the astrologer ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (903–986) for ‘Adud al-Dawla (r. 949–983), the head of the Buyid dynasty (945–1055). For his book, al-Sufi relied on an Arabic translation of Ptolemy’s Almagest, a ninth-century picture book of the constellations, several globes, as well as information on star constellations used by Bedouin tribes on the Arabian Peninsula. But al-Sufi was unfamiliar with Greek mythology. This may explain the transformation of the female head with snakes into a male head of a bearded demon (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: The Perseus constellation in an anthology compiled for Shah ‘Abbas II (r. 1642–1666) in Isfahan. Detail, Illustrated Manuscript of a Jung (Miscellany) commissioned by Shah Suleyman (1666-1692), c. 1669-c. 1670. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Philip Hofer.

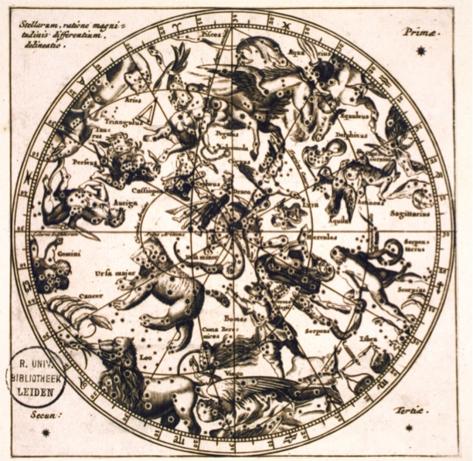

Indicators of a possible Dutch background are the fish tail of Pegasus, the flowers held by Cassiopeia, the giraffe below Cassiopeia, and the placement of Lyra on top of Corvus. Except for Pegasus’s fish tail, these elements are all found in Andreas Cellarius’s (1596–1665) map of the northern celestial sphere (Figure 3).

![Fig. 3: A. Cellarius’s map of the northern celestial hemisphere, 1660 [1708], echo.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de.](/sites/default/files/styles/content_central_image/public/2017-07/fs52_rgb_img3.jpg?itok=trNZ7_0e)

Fig. 3: A. Cellarius’s map of the northern celestial hemisphere, 1660 [1708], echo.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de.

Pegasus’s fish tail, an optical misunderstanding resulting from a map on which Pegasus and Pisces were drawn too closely together, can be seen on an anonymous and undated Dutch celestial map (Figure 4). However, this map is not antecedent to the blue map because it lacks some of its other elements.

Fig. 4: Anonymous celestial map, seventeenth century, the Northern Constellations. Leiden University Library, COLLBN Port 169 N 3.

‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi’s pictorial canon is a prime example of a creative mixture of pictorial elements from a wide range of Eurasian cultures. Near Eastern, Greco-Roman, and pre-Islamic Arabic star constellations, zodiac signs, names, and heavenly coordinates appear in early copies of al-Sufi’s book in combination with Zoroastrian, Central Asian, Buddhist, and possibly also Chinese human depictions, dress, jewelry, hairstyles, and headdresses. The cultural transformation of Medusa into a demon moved widely through Western Asia, North Africa, and parts of Europe with the book’s translations into Persian, Turkish, Latin, Castilian, and Hebrew. Yet, there is no sign that this book was ever translated into an East Asian language. Nonetheless, an East Asian planetary image could possibly be related pictorially, albeit not conceptually, to al-Sufi’s Perseus. The image in question was produced in Khara Khoto, the capital of the Tangut Xi-Xsia dynasty (r. 1038–1227), in the thirteenth or fourteenth century. The pictorial similarity between al-Sufi’s Perseus and the Tangut image of the Huibei pseudo-planet (or comet) (Figure 5) is a further enigma to be explored.

Fig. 5: Huibei (Yuebo) Planet, thirteenth to fourteenth century, St. Petersburg, Hermitage, ХХ–2450.

Other Tangut images combine Indian pictures of the nine luminaries (the sun, the moon, the five planets, and the two pseudo-planets Rahu and Ketu), images of the Mesopotamian zodiac after modification and transformation in the Greco-Roman world and South Asia, and depictions of Buddha. A text on rituals for protection against cosmic calamities recommends such images to “all monarchs, their great ministers and dependents, and the common people as a whole, who may suffer the oppression of the sun, moon, five planets, Rahu, Ketu, comets, (or other) portents and malign stars.”

Research on the heavens requires a wide range of thematic and regional expertise. Colleagues working in Departments I and III of the MPIWG collaborate in this project. Researchers at universities in Berlin, and further afield in China, Korea, Japan, India, the US, the UK, and France are also contributing to this endeavor. They study types of images from various regions, their similarities and transformations, and the educational, linguistic, political, and artistic components of their journeys through Eurasian and North African cultures.

Watch Interview with Sonja Brentjes