The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is taking a heavy toll on academic exchange, as many countries worldwide reacted to the outbreak by partially closing their borders. Taiwan implemented a particularly strict disease control regime, one developed during earlier pandemics. In addition to early travel restrictions, on April 9, 2020 the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) also announced that it would suspend all new applications from PRC students to Taiwan universities in 2020, despite the fact that many were already being processed. Many observers suggest that this new regulation is not only temporary, but is a similar restriction to the suspension of individual tourist travel to Taiwan that was promulgated in summer 2019. Both policies, they contend, resemble systematic sanctions by the government of the PRC in response to rising political tensions between Taiwan and China. This said, should it be expected that the suspension of cross-strait student exchange under the current conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic will be sustained, as a kind of coalescence of a more long-term development? Can we find hints by looking into related developments over recent years?

The Drastic Decline of PRC Students in Taiwan: Coinciding with Shifts in the Political Climate

Fig. 1. Chinese students studying in Taiwan. Source: Ministry of Education of the Republic of China (Taiwan).

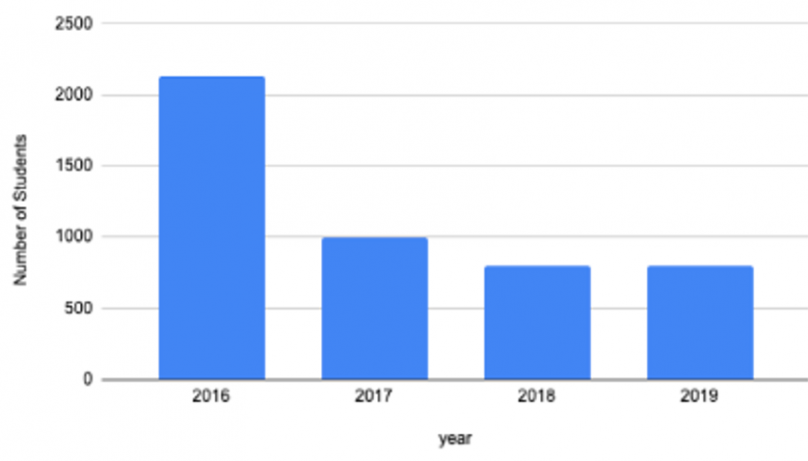

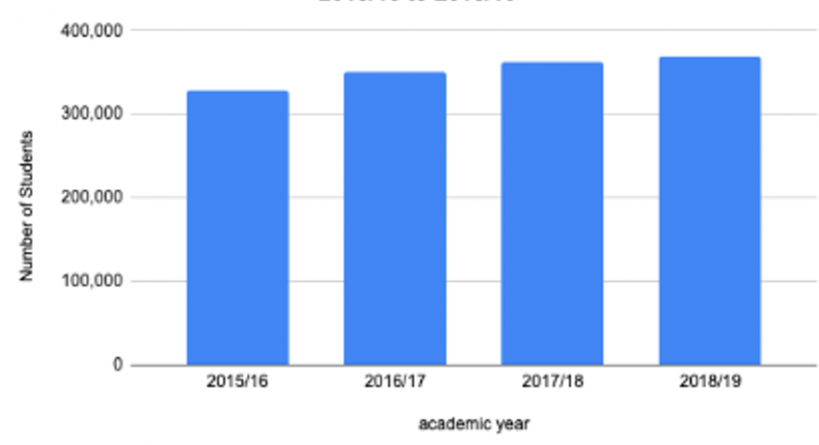

This phenomenon has structural reasons: the quota of degree students who can enroll at universities in Taiwan annually is announced by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, following a round of coordination between the two parties. “We get as many as there are,” the head of Taiwan’s University Entrance Committee for Mainland Chinese Students remarked in an interview in 2017. However, the number of admissible places in Taiwan for BA degree students from China (學士學位生), for example, has greatly decreased in recent years, from more than 2,000 available spots in 2016 to only 800 in 2019. In contrast, enrollment of Chinese students in other countries, such as the United States (see Fig. 2 and 3), shows a steady upwards trend and appears not to be regulated in the same fashion.

Fig. 2. University students from China in Taiwan, 2016–19. Source: Ministry of Education of the Republic of China (Taiwan).

Fig. 3. University students from China in the United States from academic year 2015/16 to 2018/19. Source: Open doors report from The Power of International Education.

To investigate the situation in detail, in 2016 Initium Media interviewed several presidents of universities in southern Taiwan. Many of the respondents noted the stringent control of the number of Chinese students who planned to study in Taiwan and added that it appeared to be targeting especially those universities located in communities governed by the DPP. For example, during the first semester following the 2016 election, National Cheng Kung University, which is located in one of the DPP-stronghold southern cities of Taiwan, reported that the enrollment numbers in its exchange program with Chinese universities reached only half of the average range compared to previous years. Several interviewees also stated that the tightened control of cross-strait academic exchange is used as a tool of extorting political pressure on Taiwan, and disclosed that they had received similar hints from their partner universities in China.

Driven by Economic Incentives: Pledges for Self-Censorship

The considerable profits to be made from study programs are another reason China is able to put pressure on Taiwan, by one-sidedly placing restrictions on student enrollment. The Ministry of Education of Taiwan neither sets an upper limit for student admission nor regulates tuition rates for private universities in Taiwan, which usually admit around twice as many students as public ones. Due to Taiwan’s low birthrate and a substantial chunk of income in university budgets coming from student enrollment, this flexible principle incentivizes many universities to temporarily attract students from China (陸生研修生) in order to make up for their shortage in students. On average, the tuition fee of a private university in Taiwan is around 50,000 NTD per semester (roughly equivalent to 1,700 USD). In Taiwan, the number of private university students in 2019 is two times higher than the students of public universities. Taking the 16,696 non-degree exchange students from China enrolled at private universities in 2019 as an example, the tuition fees of that year brought private universities in Taiwan at least 830 million NTD of income (about 28 million USD—calculations by the author). Along with income based on other fees, such as the rent charged for dormitories (which could range from 10,000 to 40,000 NTD; or about 340 to 1,370 USD per semester), exchange students from China therefore become a considerable source of income for private universities in Taiwan. This situation may explain why some of the university principals interviewed shied away from discussing in more detail the difficulties they have faced with student recruitment.

On the other hand, the strong incentive for universities in Taiwan to cooperate with universities in China also leads to an increase in the former’s degree of self-censorship. In 2017, Taiwanese media discovered that several universities in Taiwan signed an agreement with their partner universities in China, pledging to have no “politically sensitive” curriculum topics and not to hold any activities with content such as “Taiwan independence” or “One China, One Taiwan” during the exchange semester. After an extensive investigation, the Ministry of Education of Taiwan confirmed that at least 72 schools, almost half of the 157 universities in Taiwan, had signed a similar agreement.

Fig. 4. Agreements signed by Taiwanese universities (一中承諾書). From left to right: Shih Hsin University, St. John's University, and National Tsing Hua University. Source: Millennium, 2017, https://millenniummag.dudaone.com/20170305-1.

Disagreement and Deterrence in the PRC

Screening press reports and social media, it is noteworthy that many students in China also express their disappointment and upset feelings around the abrupt suspension of their plans for visiting Taiwan. Two days after the PRC government announced its decision to stop all new student exchanges for 2020, a student appealed to the authorities, questioning the legal basis for this new rule and its consequences. Only two months later did she receive an ambiguous official reply from the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, claiming that “no further information would be disclosed since it involves national interests.” Other reactions included a statement published by a group of Chinese students in which they mention how the reluctance of the government vis-à-vis cross-strait student exchange is also reflected in its propaganda efforts. For example, they point to the fact that it is common for the Taiwan Affairs Office (a PRC government agency) in each city to provide instructions to every student who plans to visit Taiwan before they leave China as well as when they come back during semester breaks. Whenever the political situation between Taiwan and China is especially tense, the media in the PRC, they complain, begins to portray these students in Taiwan as living under suspicious circumstances. Rumors, for example, of “a Chinese student who became a spy working for the government of Taiwan” are apparently broadcasted as a deterrence strategy in order to discourage other students from seeing Taiwan as a preferred study destination.

Latest Pandemic Regulations Also Hinder the Return of Already-Registered Exchange Students

What the current COVID-19 pandemic has again brought to the fore is the full complexity of cross-strait exchanges. While the PRC responded swiftly in announcing a travel ban for its newly-admitted exchange students, Taiwan, of course, also had to come up with its own set of ad hoc regulations steering the influx of non-tourist visitors. From mid-March, Taiwan’s borders were closed to all foreigners, with the exception of people who held Alien Resident Certificates (ARC). However, since mainland China—including Hong Kong and Macao—do not, according to the ROC’s constitution, count as foreign lands, students from these areas do not have ARCs like most international students. This restriction on the basis of visa types led to the awkward situation that—different from most registered students from other countries—current PRC students (the only exception being those with Taiwanese spouses) could not reenter Taiwan and had to wait for further instructions.

Noticeably, on August 5, 2020, two weeks after the government of Taiwan announced that all PRC degree students facing a graduation deadline (陸生應屆畢業生) were allowed to return, the authorities revealed that only a few PRC students had successfully made that trip back to Taiwan. According to the Mainland Affairs Council (a Taiwanese government agency), the PRC government apparently exerts pressure on its students who applied to reenter Taiwan through various methods. Reported cases include the obstruction of visa applications or the censorship of certain words in application certificates, such as “national” in the name of universities. Since August 24 of this year, all PRC degree students are allowed to return to Taiwan, including graduating students (應屆畢業生), continuing students (舊生), and first-year students (新生). How smooth and complete this return will be among these many tensions still remains to be seen.

Toward Uncertainty: The Complicated Future of Cross-Strait Academic Exchanges

As this short overview has demonstrated, the current hold of cross-strait student travel is obviously the culmination of a much longer trend, involving a reduction of academic exchanges happening in a highly politicized context. It remains to be seen whether and in what ways these exchanges will be taken up again after the immediate COVID-19 crisis has been tackled around the world. Is the complete stop just a momentary contingency measure, or is it a vehicle for an actual change of course? Not least for the purpose of fostering mutual understanding among the younger generations in China and Taiwan, one should hope that exchanges are revived again.

Finally, as these preliminary observations have shown, this is a topic with many facets that warrant much more in-depth research. A systematic overview of the scope and content of overall cross-strait academic exchange, including between scholars and research institutions in general, as well as the conditions for students from China studying in Taiwan and also for Taiwanese students in the PRC, will be exciting topics for future studies.