What does the sex-ratio of a population indicate? This is a question that has interested colonial administrators and scientific researchers alike, keen to understand how sex-ratios were implicated in a population’s health and reproductive capacity. During the interwar period, studies of the growth or decline of populations were the purview of a diverse group of experts—physical anthropologists, biologists, agronomists, biostatisticians, birth control activists—as demography gradually achieved disciplinary status. Though the spectre of a growing global population was cast as the dominant problem, the decline of certain populations was of concern, too. In this sense, the imbalanced sex-ratios of declining island populations in the south Pacific were of interest for what they could reveal about key scientific and imperial questions regarding the effects of “race mixing” and contact between cultures on the potential of populations.

At the landmark conferences of the International Union for the Scientific Investigation of Population Problems in 1927 and in 1932, population specialists gathered to discuss such issues that pertained to the size of populations. At the same time, the British authorities who were co-administering the Pacific island archipelago of the New Hebrides with the French, faced demands from the Protestant missionaries and scientists to ameliorate the devastating depopulation due to deaths from epidemics and low fertility rates.

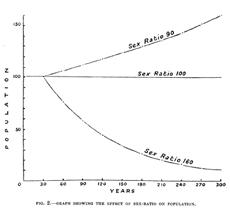

Fig. 2: Sex-ratios and population growth. John R. Baker, “Depopulation in Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides,” in: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 58 (1928), p. 293.

When they conducted rudimentary census, researchers and missionaries alike were alarmed at the imbalanced sex-ratio. Oxford biologist John Randall Baker calculated a sex-ratio of 159/100 (male/female) of an isolated population on the island Espiritu Santo during his 1925 expedition. Baker considered gendered infanticide as a cause but placed more concern with the harsher social circumstances of women compared with men and the sex-ratio at birth. The Presbyterian missionary, Dr. Maurice Frater, had conducted a census on the island of Ambrym a few years earlier and wrote about his findings to the British Resident Commissioner, Merton King. Dr. Frater claimed that the “most disconcerting feature of the census” was higher number of men compared to women. In his estimation, the imbalance and related population decline were caused by two cultural factors: “1. Early immature marriage on the part of the female. 2. The system of women purchase is not now adapted for the propagation of the race … The price of a woman on Ambrym ranges from 10-15 pigs.” Moreover, the “evil is further aggravated by old men having a plurality of wives, many of them, young women who, with husbands of a like age, would be doing their part in carrying on the continuity of the race.” Social anthropologists would later document that possessing ever more pigs was connected to successful participation in grade rank ceremonies and having the skill to develop enough social relationships to raise the pigs. Thus it took men until middle or old age to have access to that many pigs. Dr. Frater recommended that the problem be rectified by the British Resident Commissioner and strongly suggested that the chiefs forbid the marriage of young girls.

Fig. 3: Cover page of the file “The Price of Brides.” NHBS 17/I/6. Western Pacific Archives, University of Auckland Library.

Regulating the bride price and marriage practices interested the missionaries for more reasons than merely halting depopulation. The Presbyterians saw the bride price as a misplaced use of resources that was degrading to women and part of the system of maintaining alliances between expansive social groupings (which the missionaries called clans) and not the nuclear family kin relationships they wished to inculcate. As for questions of governance, the British were interested in understanding local marriage customs (which varied throughout the archipelago) in order to find an administrative solution for the registration of the diversity of marriage practices and they concurred with the missionaries’ logic. But, due to their limited means of enforcement, the British needed a measure that accommodated enough of the various “native customs” concerning marriage. Regulating—not eliminating—the bride price seemed a reasonable way to proceed. In their colonial thinking it would lower men’s marriageable age and thus increase the fertility of marriages and would work to improve the maladapted cultural practices that adversely affected women. The logic naturalized the place of reproduction in nuclear families and propagated discriminatory representations of victimized Melanesian women at the hands of aggressive Melanesian men. They achieved only sporadic success in regulating the bride price. Still, having read John Randall Baker’s research on the importance of the balanced sex-ratio, the administrators would reflect on the sex-ratio as a main indicator of population health until the 1960s.

John Baker’s methods, which involved comparing the sex-ratios of Christian villages and “heathen” villages, put his epistemic assumptions about the significance of cultural and biological isolation or contact squarely in the population discourse of the day. Since Darwin, a population’s sex-ratio became a phenomenon that might be explained by biologists through evolution by natural selection. That there was generally a balanced sex-ratio in thriving mammal populations (humans, pigs, rats, mice, and so on), was taken to indicate that it was an advantage to a population’s survival, even though it was acknowledged there were some (non-human) populations where an unbalanced sex-ratio was an advantage. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, sex-ratios were yoked to understanding sex determination at conception, differential survival of the sexes during pregnancy, sex-ratio at birth and differential survival of the sexes by reproductive age. Explanations for the sex-ratio also linked aspects of human reproductive biology with racial explanations for the variability of populations. The growing availability of censuses from around the world afforded comparative possibilities for debating environmental, cultural and heritable factors of sex-ratios. Changes in sex-ratio were taken as indicators or contributing factors pertaining to the increase or decrease of the “race”; an increase in masculinity away from the equilibrium forecast decline, while a balanced sex-ratio or more females was taken as an indicator of a stable or increasing population.

Devastated by losses of men and puzzled by the apparent increase of male births during the First World War, British researchers were preoccupied with the imbalanced sex-ratio in Britain as well. How individuals and populations responded to stress in their environments was an important consideration. Trying to explain why more males had been born during the war, Julian Huxley rejected the theory that the effect of stress on prenatal conditions might cause spontaneous abortions of the more delicate male embryos and speculated that stress converted female embryos into males. Eventually, the acceptance of the chromosome theory of sex determination in the 1920s meant that the inheritance of sex chromosome was presumed to be 50/50 and that the varying ratios needed to be explained by conditions after conception.

What did human sex-ratios indicate to British population experts and colonial administrators? To researchers interested in population issues, they were a venue to debate how cultural practices came together with biological adaptations. For British colonial administrators, the sex-ratio was a relatively easy calculation to make from even rudimentary census data, and therefore a useful measure of success in the colonial administrator’s tool kit. Both were concerned with the reproduction of different populations. Convergences of scientific questions and colonial administrative concerns on the health of diverse human groups are the focus of the international workshop “Colonial Subjects of Health and Difference: ‘Races’, Populations, Diversities” held at the MPIWG June 11-13. Organized by Alexandra Widmer and Veronika Lipphardt, the workshop is an event of the research group, Historicizing Knowledge of Human Biological Diversity in the 20th Century.