As of October 1, 771,945 people in Yemen have been infected with cholera and 2,134 have died from the disease. The epidemic, rare on such a scale in contemporary times, reemerged as a formidable force last year due to Yemen’s ongoing civil war.

The Saudi Arabia-led war began in March 2015 and has caused a spiraling 7,000 new cholera cases per day. This is an enormous public health crisis—and one that could be solved simply. Treatment only demands providing clean water, oral rehydration salts, and gloves.

These wartime conditions allow us to draw parallels with the historical experience of epidemic—after all, it is the massive displacement and conditions of war that have allowed the disease to reemerge and wreak destruction in Yemen. War has overcome the near eradication of cholera that modern advances in medicine and international public health organizations have allowed. So how did these advances come to pass and what can we learn from the historical experience of cholera?

A patient drinks oral rehydration solution in order to counteract cholera-induced dehydration, 1992. Wikimedia Commons.

Cholera Imagined

We first find mention of a disease that is recognizably cholera in the works of Arab-Islamic scholars, where it is known of as “heydain.” Around 900 CE, the physician Muhammad ibn al-Razi described cholera in the following way:

"It begins with nausea and diarrhea, or one of the two, and when it reaches the stomach it goes on multiplying itself. The pulse fails, and the breathing is attenuated; the face and the nose become thin; the color of the skin of the face is changed, and the countenance of the dead succeeds."

Despite this long history, cholera was, in particular, a nineteenth century tragedy. The disease, which travels through water, thrived on the world’s multiplying population and increased mobility. During the first cholera pandemic (1817–1823), the disease traveled across the Persian Gulf from Bahrain along the Indian Ocean and to the Red Sea in Aden. Over the course of the century, multiple outbreaks of the disease quickly spread through burgeoning coastal cities, along rivers, and into commercial ports from Delhi to New York City.

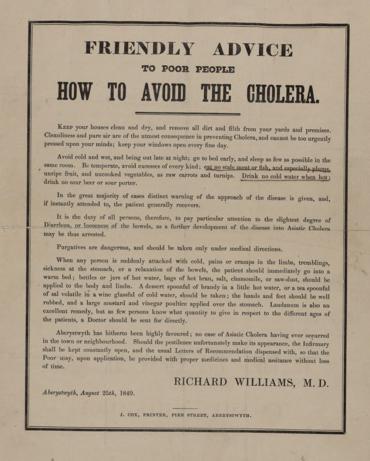

How to avoid the Cholera, 1848. Wikimedia Commons.

Medical and public health practitioners such as physicians and midwives played a major role in reducing transmission in the period. These people and institutions were financed through religious taxes and charity, which provided more resources to directly treat patients.

Public Health Reforms

But it was the emergence of modern medicine, the improvements on sanitation, and the isolation of Vibrio cholerae in 1854 by Filippo Pacini that worked to drastically ameliorate cholera’s impact in the latter half of the century.

The repeated outbreaks also arguably led to the creation of the kinds of public health institutions that we take for granted today. The International Sanitary Convention (ISC), which held its first conference in 1851 in Paris, was set up with the aim of ending the cholera pandemic. The ISC was a predecessor to the World Health Organisation (WHO), a body that was mostly represented by European actors along with the Ottoman central authority (based in Istanbul).

Vibrio cholerae. Wikimedia Commons.

Although the cholera epidemic was still rampant on the Arabian peninsula during the early twentieth century, with outbreaks in Mecca between 1908–1912, the disease was then nearly totally absent from the peninsula until it spread in Yemen in 1971—following the aftermath of the last Yemeni civil war.

Yemen witnessed cholera outbreaks in the nineteenth century due to the free movement of people and a very limited understanding of the disease. But the conditions and ways that the disease spread was nowhere near as quick-paced and detrimental as they are in the current outbreak.

Cholera Today

The human cost of cholera in Yemen today, as we have seen, is grave and growing. There are predictions that the disease could infect a million people by 2018. The incidence and prevalence of cholera infection far exceeds the numbers from the nineteenth century and the current crisis in Yemen will set a record number of reported cases in the country.

What makes the current epidemic so pernicious is the way that war has exacerbated the disease despite advances in medicine and public health. The doctors and nurses working in the nineteenth century were not mired by the catastrophic conditions of modern war: massive military occupation, infrastructure meltdown, and political decimation.

The Yemeni government ceased providing money for the public health department in March 2016, shortly after war began. International organizations have provided the principle support, but the amount they can do is limited by their ability to carry out treatment during military sieges. Less than 50 percent of hospitals in Yemen are operational, with shortages of staff and supplies due to the ongoing conflict. But austerity and war have fractured the public health system. The 30,000 doctors, nurses, and other health care workers of Yemen have been working for the last ten months without pay.

The treatment for cholera is very simple, yet materials—when available—are obstructed from being distributed due to bombing. The arc of authoritarianism and foreign occupation in Yemen has resulted in the destruction of Yemen’s infrastructure, leaving four million people without access to clean water.

History provides a glimpse of the tragic past and demonstrates that it is through policy that we can help to correct the tragedies that continue to face Yemen. Cholera is preventable, but public health reform is nearly impossible under conditions of war. The historical trajectory of cholera shows that interventions lose their effect when the public systems are crippled—something we also need to bear in mind in relation to the increased extreme weather events caused by climate change.