In 2021, Danish media flagged that a Chinese professor at the University of Copenhagen, Guojie Zhang (张国捷) published an article with co-authors who had links to the PLA. Their paper examined monkey brain damage in high-altitude areas in the Tibetan Plateau. The media, security authorities, and the broader public were enraged by the fact that a top European university was working with the Chinese army. Zhang himself denied the accusations, saying that none of his research is related to military purposes: “This is just normal basic research, and all the information is publicly available. Besides the research and its result, there is nothing worth paying attention to.”

Judging him on his scientific merit, Guojie Zhang belonged to the most productive researchers of Chinese origin in Europe. As one of the most cited scientists in the world, he sports an impressive research output having published twenty articles in Nature or Science as the leading author. Around the time of the incident, Zhang moved his lab to Zhejiang University in Hangzhou. His case was just one of many in recent years, raising critique due to the ethical issues and legal regulations pertaining to research security. He is also not the only high-profile scientist to return to China. Recent examples include Yau Shing-Tung (丘成桐), a mathematician and a winner of the Fields Medal, who moved from Harvard to Tsinghua in 2022 and Yan Nieng (颜宁), a biologist who ditched her tenure at Princeton for Shenzhen. Reverse migration is more than just an outcome of geopolitical rivalries, as family reasons, personal preferences, and career development opportunities all play a role. However, the political situation does seem to contribute to many scientists’ choices whether to move (back) to China. While 900 scientists moved from the US back to China in 2010, 2,621 did so in 2021, a 75% higher departure rate than in 2018. This date coincides with the launch of the China Initiative.

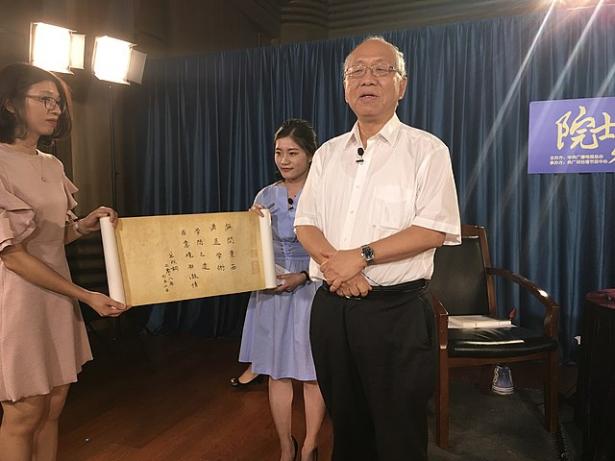

Yau Shing-Tung (丘成桐) featured in the CCTV program “Academicians are here!” (院士来了). The first Chinese winner of the Fields Medal moved from Harvard to Tsinghua in 2022. (Source: Ye Youjia 葉又嘉/Wikimedia Commons 2018).

Several investigations, carried out mostly by the media, security and intelligence agencies, government officials, and think tanks, have played a key role in exposing links between the Chinese Party-state and the Anglo-American and European academia. The investigations have interrogated scientific practices for potential espionage, IP theft, human rights abuses, export controls violations, and dual-use technology. This development has called into question aspects of academic work that used to be automatic and unregulated. Researchers with formerly thriving careers were put under investigation, which questioned their research integrity and the legality of their actions. The 2023 UK Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) report demonstrates this change: “China operates a number of Party and state-sponsored talent programmes to recruit researchers (both Chinese and non-Chinese nationals), who are then incentivized to steal foreign technologies needed to advance China’s national, military, and economic goals.”

In my research on Europe-China research collaboration, I have heard remarks echoing both Guojie Zhang and the ISC report countless times. They reveal an interesting puzzle: The academic perspective shared by many natural scientists stresses scientific outputs as innocent, publicly available, and without commercial or military implications. They argue that a) their research is basic, without immediate applications b) science is apolitical and transcends national interests, and c) securitization of research harms a free exchange of ideas and scientific progress. Their statements stand in stark contrast with the dominant political perspective across the Western democratic world which, in reaction to Chinese state policies, emphasizes that a) science “made in China” is applied, serving practical usage, b) it has political objectives, and c) the securitization of research collaboration is necessary to protect national security, economic resilience, and academic freedom. This short piece cannot address the complexity of the topic. Instead, it will focus on the discrepancy that unfolded in recent years: Exposed to a geopolitical stress test, scientists’ own accounts of their behavior are in contrast with how non-scientists interpret academic work. In this short article, I explore two potential explanations behind this clash of perspectives, one theoretical and one methodological. I show that while the theoretical explanation supports the scientists’ viewpoint, the methodological explanation casts doubt upon it. In doing so, I also show how social science about China can help further unpack this idea.

Competing Logics of the State and Academic Profession

My first standpoint comes from new institutional theory, and its approach to how rules, norms, and values underscore collective action. The institutional logics approach treats institutions as patterns of activity which ascribe society appropriate behavior. It identifies organizing principles (logics) as ideal types of societal orders: The state, profession, community, religion, family, market, and corporation. In this text, I focus on the interplay between two: the state and the profession. The profession logic posits people striving to enhance their status in their professional community by improving their craft. On the other hand, the state logic emphasizes the regulation of human activities via the state’s bureaucratic apparatus, redistribution of public resources, and protection of national interest. By doing so, the state impacts the functioning of all organizations and individuals located on its territory.

Researchers like Guojie Zhang are primarily driven by the logic of the academic profession, which commands them to work with anyone who shares their research interest. International research collaboration creates ideas vital to push the boundaries of knowledge while also developing scientists’ expertise and careers. In doing so, natural scientists follow the norms in their field, which are closely measured by the number of publications and their impact factors. Although Chinese academia is strongly regulated by the state and the CCP, natural scientists are mainly driven by the profession logic and mostly adhere to international norms.

The logics of the Chinese state and academic profession on display at Tongji University in Shanghai: “Study (Xi Jinping) thought, strengthen the Party spirit, stress implementation and achieve new contributions!” (Andrea Braun Střelcová 2023).

However, the social world is complex, so multiple logics operate at the same time—sometimes in line with and sometimes against each other. During the Reform and Opening era, the “engagement ethos” was prevalent, and through exchanges and funding calls Western scholars and universities were incentivized to develop links with their Chinese counterparts (and vice versa). Back then, the logics of the academic profession and state were aligned. During that time Chinese scientists in the West (and foreign scientists in China) were seen primarily as “bridge-builders,” without any hint of suspicion. They were encouraged to create stronger academic ties between Western and Chinese research communities. However, after the arrival of Xi Jinping, it became slowly apparent that the two state ideologies, underpinning the Chinese authoritarian and in the Western liberal democratic policies, were drifting apart. Gradually, the US and China ended up in competition—and ultimately rivalry. The focus on national security began to dominate the state logic, spilling over into science. This resulted in an overt clash between the academic profession and the state logic, catching scientists, like Guojie Zhang, in the crosshairs.

A Clash of Attitudes and Behavior

Qualitative research methodology offers a second perspective to interpret the scientists’ claims. Social scientists have long questioned modern society’s dependency on interviews—conversations that unravel individual emotions, experiences, perspectives or attitudes. Interviews, as a means of communication, are ubiquitous among journalists, podcast and talk show hosts, marketing professionals, psychologists, therapists, social scientists, and the general public. Although they are often taken as a truthful description of a person’s behaviour, interviews are not objective knowledge claims. Numerous biases and distortions arise, depending on the relationship between the interviewee and interviewer, as well as the purpose of the interview, its target audience, the language used, etc. Interviewees may not recall past events or they may choose to omit inconvenient parts of their story to make an impression on the interviewer. Moreover, insincerity is appropriate in some cultures or situations, such as towards outsiders or people of different social statuses etc. Some cultures prefer affirmative answers to preserve societal coherence or hierarchy. Even in cultures with a high level of trust, being vague is appropriate in some situations to maintain respect. In short, the gap between a person’s public attitude and their actual behaviour (what they say they do vs. what they actually do) can be rather large.

Interviews are omnipresent in modern societies, including in China. World Economic Forum event “How Innovation Grows,” Tianjin, 2016. (Source: Flickr/Sikarin Thanachaiary).

The difference between what is said and what is done is even stronger among politicians, where lying is widespread. But even scientists who claim their research is basic, may be, willingly or unwillingly, muddying the political aspect of their work or its application potential. They may distort elements of their behavior to people from outside their academic community. Their scientific culture also does not demand they reflect about politics and national security. Whatever the individual motivation, they may choose to emphasize the collaborative character of research for the public good, and downplay its competitive or political aspects.

Social Science as A Way Out

As Zhang’s story testifies, the official and public perception of what is a legal, ethical, acceptable, or desirable research collaboration with Chinese scientists has notably changed in the West in recent years. The nuts and bolts of academic work carried out with researchers and organizations in mainland China, previously discussed in confided scientific communities, are now in the public spotlight. This shift is visible in the gap between some scientists’ public attitude, and non-scientists’ interpretation of academic work.

In this short piece I have offered two possible explanations for the clashing perspectives between scientists and non-scientists. The theoretical explanation shows that the geopolitical shift has changed the context framing scientists’ actions, by putting their dominant logic (academic profession) in competition with the state logic. This explains why academics with links to Chinese academia see their work as apolitical, benefitting the global scientific community, while outsiders to science may interpret the same actions as harming national security. The second explanation is a methods-inspired one, which points out that the scientists’ remarks, defending their research as basic, show merely their public attitude, not necessarily their behavior.

These are only two possible avenues to examine how the geopolitical environment affects global research collaboration. Considering that science is made by people which can in turn reflect their context, and each scientific discipline is different, there are numerous approaches to explore this topic in future research. If we want to know what the scientists’ actions are, we cannot just rely on their statements, especially in a volatile political environment. Instead, we need to observe their behaviour. Suitable methods, such as ethnography, can be triangulated with interviews, archival research, and other methods from STS, China studies, anthropology, or other social science disciplines. Accessible research sites in China are hard to reach, but the influence of politics on science “made in China” still deserves our close attention. Future research may also revisit where basic research ends and applied research begins, and whether China is to blame for blurring the distinction. Who gets to define what the acceptable academic norms are in the era of US-China rivalry, given the vast diversity of practices in different scientific disciplines, is another question that deserves to be studied further.