But thanks to the internet, an almost inconceivable amount of sources are now available to the historian. The basis of historical research—manuscripts, rare books, images, and documents of a private and administrative nature like letters and financial plans—can now be accessed from almost everywhere. And this increased quantity of available historical sources doesn’t just mean that we now know it better. It means that now, we can know it differently. This quantity has affected the nature of our research. It has not only changed the kinds of answers historical study can provide, but also what questions we ask.

History comes in two flavors. There’s what I call micro history, and then there’s long-durée historical reconstruction. The first is characterized by detailed but temporally and spatially limited case studies; the second is rather a second-order reflection oriented by a historical hypothesis. This sort embraces a long spatial and temporal span but is informed by a limited number of selected case studies.

This has long restricted the kind of history that can be studied. But by mathematically analyzing large historical data sets, it becomes possible to integrate the two approaches, conducting deep source analysis systematically while covering long spatial and temporal distances. In the field of history of science, which I work in, this is allowing us to investigate how the scientific knowledge systems that now dictate our lives formed.

Why is this possible? First, because the selection of sources against which historical hypotheses are proved, modified and sometimes rejected has increased. But also because such an increased number of sources allows for the consideration of more perspectives simultaneously.

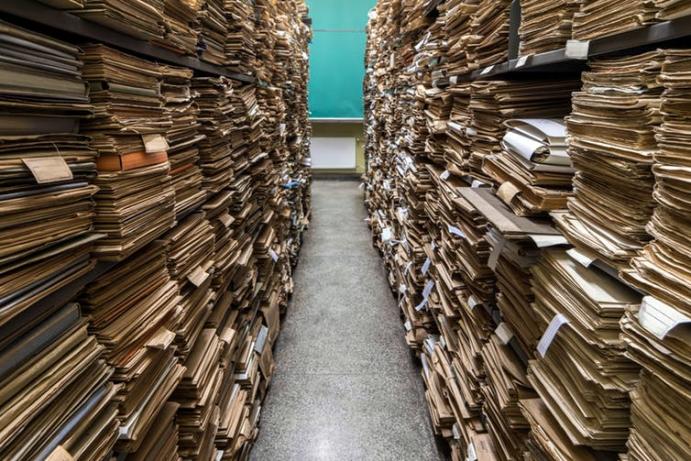

These new methods allow historians to analyse far more and varied data than was previously possible. Pakula Piotr/Shutterstock.com.

A New History

For instance, historians of knowledge can now not only consider a much larger corpus of sources, such as a large quantity of scientific treatises from the past, but also the sources concerned with the institutional, economic, and social context in which such treaties were produced. Historians have long called for a contextualized history of knowledge, but until now, long-durée historical reconstructions could only connect a few well studied examples by means of specific hypotheses of an economic or conceptual nature.

But if a much larger corpus of sources is able to be considered and analyzed in detail, we can reflect more broadly about mechanisms of knowledge evolution. This allows us to move toward a more abstract understanding of our past. We can speak about the mechanisms of history—and other humanities—in a totally new, informed way.

An entire new discipline—the digital humanities—emerged in order to allow scholars to manage this wealth of information. Historical sources, their electronic copies and bibliographic metadata are increasingly immersed in a frame of annotations, ideas, and relations electronically produced by historians while studying our material and intellectual heritage. Appropriate repositories have been created for all this data and a standard format for its preservation and reuse independently from these platforms and tools is being developed.

Open access to data, even more than to publications, is therefore becoming imperative. History writing is leading the humanities to contribute to that new frontier of science called big data.

Historian-Mathematicians

So historians now have to get their heads around mathematics, too. While a database is never much more than an expression of arithmetic or linear algebra, the increasing amount of available data is calling for a more sophisticated approach. By joining force with sociology, history writing is now entering a new phase, characterized by the application of algorithms and work flows borrowed from the field of social network analysis.

An example of a social network visualisation. Grandjean Martin, CC BY-SA.

For example, the historian Ingeborg van Vugt has used this multi-layered approach to explore the different ways in which information circulated in the Republic of Letters, the long-distance intellectual community of the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and America. Such research allows us to better visualize how the Age of Enlightenment, driven forward by these intellectuals, developed. The next step could be to statistically model this network, and so be able to pursue her research question by integrating an even broader wealth of data.

A network model for studies in history of knowledge has to consider an unusually varied set of data. There is the data of a social nature concerned with people and organizations; that concerned with material aspects of history, such as the conservation life of a book; and the data that represent the actual knowledge, the content of the sources. These are three different levels of one and the same evolving network for which explanatory mathematical models have been rarely conceived and even less realized. From this perspective, history writing is even about to challenge applied statistics.

Although mathematical modelling in the frame of history is clearly at its first steps, its introduction already appears unstoppable. This is creating the conditions for the emergence of a new vision, according to which we might be able to develop general mathematical models to explain how ideas and knowledge changed from a social and historical perspective. Perhaps we could even use these models in different areas of scientific research dedicated to the present and the future. And in such a future, humanities and exact science will begin to use the same mathematical language.