It examines the evolutionary role of knowledge going back to the dawn of civilization while providing vital perspectives on the complex challenges confronting us today in the Anthropocene—this new geological epoch shaped by humankind.

Princeton University Press, 2020.

Rethinking science for the Anthropocene means asking a number of fundamental questions about science and knowledge, and about their historical evolution: What has led us into the Anthropocene? And how can we live responsibly in this new geological age? This book addresses these questions from a novel perspective—the role of knowledge in ongoing global transformations. Its story is anchored in the research pursued in Department I of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science since its foundation in 1994. It encapsulates the investigation of the history of science as part of a larger history of human knowledge, emphasizing the role of practical knowledge and historical continuity. In looking at knowledge in terms of its long-term transmission and transformation, and at the processes of its transfer and globalization, we make use of these investigations to help us understand how humanity has now arrived in the Anthropocene.

A definitive answer to the question of when the Anthropocene began is still under discussion. This timeline presents some of the proposals. Chris Reznich.

Making Sense of the Evolution of Knowledge

How can one pursue such a comprehensive and multidisciplinary endeavor as the evolution of human knowledge? The approach taken in this book may be likened to the strategy of a film producer adapting a complex novel into a simplified script for a movie: reducing the number of characters and narratives and concentrating on a few, carefully selected key figures and themes, suited to investigations of both the long-term developments and the global transformations of knowledge. The book analyzes key episodes such as the evolution of writing, the emergence of science in the ancient world, the Scientific Revolution of early modernity, the globalization of knowledge, industrialization, and the profound transformations wrought by modern science.

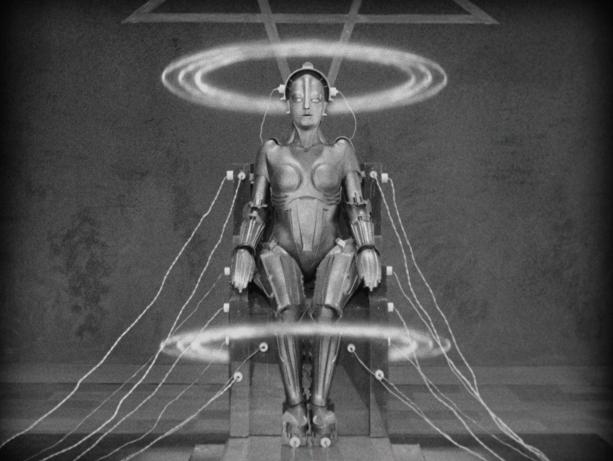

Maria, the android, in Fritz Lang’s expressionist 1927 film Metropolis, one of the first robots featured in cinema and an early forerunner of the notion of artificial intelligence. The film was inspired by a 1925 novel of the same name by the German writer Thea von Harbou. Walter Schulze-Mittendorff—WSM Artmetropolis.

The History of Mechanical Knowledge

One narrative strand that lends itself to this strategy is the history of mechanical knowledge. Mechanical knowledge has a history extending from the elementary and intuitive knowledge of prehuman history, the long tradition of practical experience with tools and instruments, to theoretical forms of knowledge as documented in written texts, and the latest developments that include the new mechanics of relativity theory and quantum mechanics. Another relevant feature of mechanical knowledge is the fact that it is not exclusive to the Western tradition but has flourished in other cultures across time.

Archimedes and Hero of Alexandria as role models for the early modern engineer. Salomon de Caus, Les raisons des forces mouvantes, 1615.

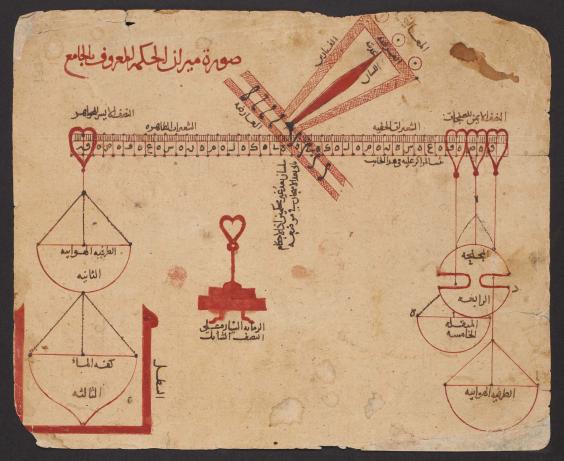

Specific investigations have been dedicated to the varying levels of mechanical knowledge: from the use of simple machines, such as the lever or pulley, to the formulation of highly abstract theories, such as that of quantum mechanics. The investigations cover time periods ranging from antiquity to modern times, and include cross-cultural comparisons, in particular between Western, Chinese, and Islamic science. Special attention was given not so much to individual discoveries and achievements as to the broader social processes enabling the transmission, accumulation, and innovation of knowledge, including its losses and the dramatic changes that the cognitive and social structures of this knowledge underwent over millennia.

The image depicts the Balance of Wisdom with its parts as described and explained in a thirteenth-century manuscript of a book by ʻAbd al-Raḥmān Khāzinī (c. 1121). MS LJJ 386, Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection of Manuscripts, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.

Further investigations have dealt more broadly with how modern physics emerged, taking the work of Albert Einstein on relativity theory and the history of quantum physics as focal points. Other strands of research were dedicated to an “epistemic history” of architecture, from the Neolithic age to the Renaissance, and to the historical epistemology of space, looking at the interaction of experience and reflection in the historical development of spatial knowledge, from primate cognition to modern science.

Essential documented chronology of the Cupola of S. Maria del Fiore. From M. Haines, “Myth and Management in the Construction of Brunelleschi’s Cupola.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 14/15:47–101 (2011–2012, 99).

The Globalization of Knowledge

A comprehensive investigation on the globalization of knowledge and its consequences has examined processes of cross-cultural knowledge circulation. This encouraged the exploration of new methodological approaches to questions of knowledge transfer and dissemination, in particular the use of social network analysis. Since the history of scientific knowledge can only be understood against the background of other, more basic forms of knowledge, studies of intuitive and practical knowledge, Western and otherwise, have also been pursued. Comparative field research was undertaken, for example in Papua New Guinea and Germany, where the development of intuitive conceptions of force, motion, weight, and density were analyzed. An array of disciplines and methods has been employed in this context, from cognitive science and experimental psychology to evolutionary biology. The result is a new framework for understanding structural changes in systems of knowledge—and a new approach to the history and philosophy of science.

Tapestry: Astronomy, from the L’Histoire de l’empereur de la Chine series, wool and silk, Beauvais manufacture, 1722–1732. The templates were designed between 1686–1690 under the direction of Philippe Behagle (1641–1705). In the center the Chinese Emperor Shunzi (1638–1661), on his right side the Jesuit court astronomer Adam Schall von Bell (1592–1666), the teacher with the child are probably his and Johannes Schreck’s (1576–1630) successor, the Jesuit astronomer Ferdinand Verbiest (1623–1688) with the son of the Emperor Kangxi (1654–1722). Inv.Nr. BSVQ0140. Bamberg, Neue Residenz mit Rosengarten, Room 10 c Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung.

Future Challenges of the Anthropocene

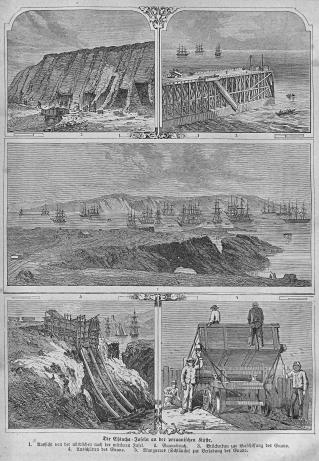

But how can such long-term and expansive investigations relate to the challenges of the Anthropocene? One example is given by a study of the development of the synthesis of ammonia, dealing with its prerequisites, its invention, and its consequences. This milestone in the history of chemistry led not only to a transformation of knowledge, but also of the related social structures; it revolutionized agriculture worldwide, defining new fields of research, technology development, and economic productivity. The substitution of natural resources such as saltpetre and guano by chemical products is regarded as one of the crucial phases for the onset of the Anthropocene. The accumulation of new human knowledge has led to the massive intervention in various Earth system cycles, such as the carbon cycle, causing climate change, as well as the water, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur cycles, all of which are fundamental to life on Earth. Understanding the evolution of such knowledge can reveal our pathways into the Anthropocene and may help us to make informed choices in strategies for dealing with its future challenges.

A plate from Die Gartenlaube, 1863 showing guano collection on the Chincha Islands off the Peruvian coast. Guano, a word rooted in the Quechua language, designates the accumulated excrement of seabirds and bats. It contains high amounts of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium and is therefore a highly effective fertilizer.

Between the military and science during World War I. Fritz Haber (inventor of the Haber-Bosch process for synthesizing ammonia and “father of chemical warfare”) pointing to canisters containing chlorine gas with Oberst Leopold Goslich of the German Gas Pioneer Regiment, and Officer Fuchs at the left (1914–1918). Courtesy of the Archive of the Max Planck Society, Berlin-Dahlem.

This book investigates the double character of knowledge crucial for our entry into the Anthropocene, the empowerment it provides, and the unintended consequences it leads to. It looks at the historical nature of thinking, the diffusion and globalization processes of knowledge, and the ways in which knowledge structures in turn change and affect society. All of these various strands of investigation, dealing with different historical epochs, are related back to the theme of the Anthropocene, discussing its emergence against the background of evolutionary considerations and looking at what knowledge our future could depend on. In doing so, it encourages historians to forge new alliances with scientists and to seek new methodologies that involve more comparative and systemic perspectives.

Water quality in the Northeast, Upper Mississippi River Basin and Great Lakes Basin are at the highest risk in the US as nitrogen runoff increases with more intense rainfall. Robert Ashworth/CC-BY-2.0.

The approach to the history of knowledge developed in this book will be presented in more detail in at the Institute’s Colloquium at the MPIWG, date to be announced.